Then I smoked my pipe and to clear my mind read idly enough, I fear, some philosophical treatise that was not too heavy to hold in one hand. The first lot of mules had already got away, and now my bedding was rolled up, the things I had used for breakfast were put into the proper boxes, and everything was loaded on such of the mules as had remained behind. I let them get ahead. I was left alone in the bungalow, my pony tethered to a fence, and I watched with the eyes of my mind, so to say, while the village about me, the trees outside the bungalow, the chairs and tables, returned to the humdrum repose from which for a few hours the arrival of myself and my caravan had rudely snatched them. When I went down the steps and untethered my pony, silence, like an old mad woman with a finger on her lips, crept past me into the room that I had left. The map of the road hung on its nail more solidly because I was gone and the long chair in which I had been sitting gave a creaky sigh.

I started riding.

I caught up with the mules as they were nearing the bungalow and knowing it was close the increased their pace. They went along now with a sort of bustle, the bells ringing, the loads jangling, and the muleteers shouted to them and called out to one another. The muleteers were Yunnanese, strapping fellows, with bronzed faces, ragged and unwashed, but they bore themselves with a bold insouciance. Up and down Asia they marched with a lazy stride, hundreds upon hundreds of miles, and in their dark eyes were open spaces and the dim blue of far-off mountains. The mules crowded round them in the compound, each wanting his own load taken off first, and there was a shouting and a kicking and a jostling. The load is lashed to the yokes with leather thongs and it needs two men to take it off. When this was done the mule retrated a step or two and bowed his head as though he were bowing his thanks for the release. Then the pack-saddle was taken off him and he lay down on the ground and rolled over and over to ease his back of the irritation. One after the other as they were freed the mules wandered out of the compound to the herbage and their liberty.

Gin and bitters waited for me on the table, then my curry was served, and I flung myself in a long chair and went to sleep. When I woke I went out with my gun. The headman had designated two or three young men to show me where I could shoot pigeon or jungle-fowl, but game was shy and I am a bad shot and I came back generally with nothing for my pains but a scramble in the bush. The light was failing. The muleteers called the mules to shut them up for the night in the compound. They called in a shrill falsetto, a sound wild and barbaric that seemed scarcely human; it was a peculiar, even a terrifying cry, and it suggested vaguely the vast distances of Asia and the nomad tribes of heaven knows how many ages back from which they were descended.

I read till my dinner was ready. If I had crossed a river that day I ate a bony, tasteless fish; if not, sardines or tunny; a dish of tough meat, and one of the three sweets that my Indian cook knew how to make. Then I played patience.

I reproached myself as I set out the cards. Considering the shortness of life and the infinite number of important things there are to do during its course, it can only be the proof of a flippant disposition that one should waste one's time in such a pursuit. I had with me a number of books that would have improved my mind and others, masterpieces of style, by the study of which I might have made progress in the learning of this difficult language in which we write. I had a volume, small enough to carry in my pocket, that contained all the tragedies of Shakespeare and I had resolved to read one act of one play on every day of my journey. I promised myself thus both entertainment and profit. But I knew seventeen varieties of patience. I tried the Spider and never by any chance got it out; I tried the patience they play at the Florence Club (and you should hear the shout of triumph which goes up when some Florentine of noble family, Pazzi or Strozzi, accomplishes it) and I tried a patience, the most incredibly difficult of all, that was taught me by a Dutch gentleman from Philadelphia. Of course the perfect patience has never been invented. This should take a long time to do; it should be complicated, calling forth all the ingenuity you have; it should require profound thought and demand from you solid reasoning, the exercise of logic and the weighing of chances; it should be full of hairbreath escapes so that your heart palpitates as you see what disaster might have befallen you had you put down the wrong card; it should poise you dizzy on the topmost peak of suspense when you consider that your fate hangs on the next card you turn up; it should wring your withers with apprehension; it should have desperate perils that you must avoid and incredible difficulties that only a reckless courage can surmount; and at the end, if you have made no mistake, if you have seized opportunity by the forelock and wrung unstable fortune by the neck, victory should always crown your efforts.

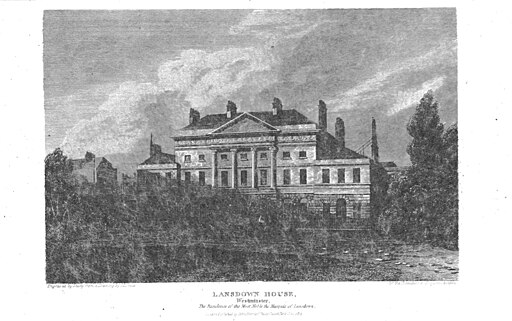

But since such a patience does not exist, in the long run I generally returned to that which has immortalised the name of Canfield. Though it is of course very difficult to get out, you are at least sure of some result, and when all seems lost the turning of a sudden happy card may grant you a respite. I have heard that this estimable gentleman was a gambler in New York and he sold you the pack for fifty dollars and gave you five dollars for every card you got out. The establishment was palatial, supper was free and champagne flowed freely; negroes shuffled the packs for you. There were Turkey carpets on the floors and pictures by Meissonier and Lord Leighton on the walls, and there were life-sized statues in marble. I think it must have been very like Lansdowne House.

Looking back on it from this distance it had for me something of the charm of a genre picture and as I set out the seven cards, and then the six, I saw from my quiet room in the jungle bungalow (as it were through the wrong end of a telescope) the rooms brightly lit with glass chandeliers, the crowd of people, the haze of smoke and the tense, strained, tragic feeling of the gambling-hell. I was held for a moment in the great world with its complications, vice and dissipation. It is one of the mistakes that people make to think that the East is depraved; on the contrary the Oriental has a modesty that the ordinary European would find fantastic. His virtue is not the same as the European's, but I think he is more virtuous. Vice you must look for in Paris, London or New York, rather than in Benares or Peking. But whether this is due to the fact that the Oriental, not being oppressed as we are by the sense of sin, feels no need to transgress the rules that during the long course of his history he has found it convenient to make, or whether, as is shown by his art and literature (which after all are only complicated, but monotonous variation on a single theme) he is unimaginative, who am I to say?

It was time for me to go to bed. I got under my mosquito curtain, lit my pipe and read the novel which I kept for that particular moment. I had looked forward to it all day. It was Du Côté de Guermantes and in my fear of coming to the end of it too quickly (I had read it before and could not really start on it the moment I had finished it) I limited myself rigidly to thirty pages at a time. A great deal of course was exquisitely boring, but what did I care? I would sooner be bored by Proust than amused by anybody else, and I finished the thirty pages all too soon; I seemed to have to hold back my eyes not to run along the lines too quickly. I put out my lamp and fell into a dreamless sleep.

But I could have sworn I had not been asleep ten minutes when a cock, crowing loudly, woke me; and the various sounds in the compound, first one and then after a pause another, broke in upon the silence of the night. The gathering light crept into my room. Another day began.

+-mymaughamcollection.blogspot.com-+ | | | | \|/ | | \~|~/ | | ,#####\/ | ,\/§§§§ | | # #\./#__|_§_\./ | | # \./ # _|_§ \./ | | # #/ # | § \ | | # # # | `~§§§§§ | +--------mmccl.blogspot.com--------+